Suspect XLH?

Connect their symptoms and accurately diagnose with the right tests.

Case summary

Findings/outcomes

*The information for this case study was provided courtesy of Dr. Anthony Portale, Director of the Pediatric Dialysis Program, UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital, San Francisco. This case study represents a real patient and is intended to be illustrative, not a recommendation for treatment or management. This case study does not claim to represent typical results.

Although X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH) is primarily an inherited disease, 20% to 30% of cases arise spontaneously.1,2

Medical history

18-19 months: Pediatric evaluation

28 months: Orthopedic evaluation

29 months: Genetics evaluation

31 months: Endocrinology evaluation

†The reference percentiles on the graph are combined from the 2 clinical growth charts for females 2-20 years of age provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

History of growth progression:

Diagnosis and initial treatment

For patients with XLH, the diagnosis process can be long and laborious, and proper specialist referral can be key to early disease management.

Disease progression

39 months: Nephrology follow-up evaluation

54 months

54 months

Laboratory results

| Test (reference‡ range unit) | 31 months (results) | 54 months (results) |

|

Serum phosphorus (4.3-6.8 mg/dL) |

2.9 | 2.5 |

| TmP/GFR (4.0-5.2 mg/dL) | 2.4 | n/a |

| 25(OH)D (≥20 ng/mL) | 41 | 31 |

| ALP (<156-369 U/L) | 461 | 404 |

| Serum calcium (9.2-10.5 mg/dL) | 9.4 | 9.9 |

| PTH (<10-65 pg/mL) | 57 | 31 |

‡Indicates normal range, age, and sex matched. Note that normal range values may vary depending on reference dataset. The ranges in this table were provided by the treating physician. Colored values are outside of the normal range provided by the physician and can raise suspicion of XLH.

25(OH)D=25-hydroxyvitamin D; ALP=alkaline phosphatase; PTH=parathyroid hormone; TmP/GFR=ratio of tubular maximum reabsorption of phosphorus to glomerular filtration rate.

This patient’s disease symptoms continued to progress despite therapy with oral calcitriol and potassium phosphate.

Case summary

Findings/outcomes

Symptoms of XLH are nonspecific when considered individually and vary between patients. Specialist referral is key to early disease management.

Medical history

Birth

12 months

Family history

30 months

34 months: Key fasting laboratory findings (reference range∥)

||Indicates normal range, age, and sex matched. Note that normal range values may vary depending on reference dataset. These ranges were provided by the treating physician. Colored values are outside of the normal range provided by the physician and can raise suspicion of XLH.

¶The reference percentiles on the graph are combined from the 2 clinical growth charts for girls 2-20 years of age provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

History of growth progression:

Diagnosis and initial treatment

Disease progression

1-3 years of age: Managed under orthopedic care

3 years of age: Referred to endocrinology

5.9 years of age

Although this patient’s laboratory results improved, there was no height velocity increase. At 3 years of age, it was concluded that biochemical optimization was not met; patient was then seen monthly to tailor therapy.

7 years of age: Metabolic bone disease under control

3-9 years of age

9.5 years of age

As this patient matured, awareness of disability and obvious orthopedic deformities increased. Regardless of provider, asking about her mental health was an important element of care.

10 years of age

Between 12.5 and 14.5 years of age

Once growth potential was reached, XLH management continued, including monitoring of biochemical bone health to promote healing and peak bone mass. As the patient aged, her disease management transitioned from promoting bone growth to fracture prevention and maximizing musculoskeletal health.

Case summary

Findings/outcomes

#The information for this case study was provided courtesy of Dr. Kathryn McCrystal Dahir, Professor of Medicine, Department of Endocrinology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville. This case study represents a real patient and is intended to be illustrative, not a recommendation for treatment or management. Results may vary. This case study does not claim to represent typical results.

It is important to diagnose XLH accurately and early, as the progressive nature of XLH leaves patients susceptible to short stature, fractures, limited function, and pain.1,5,6

Medical history

During childhood

Early to mid-20s

44 years of age

Family history

Physical exam

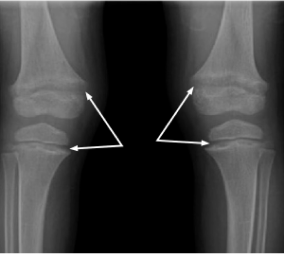

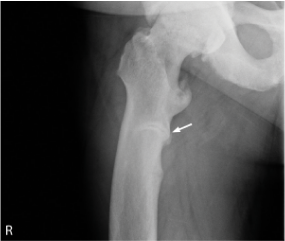

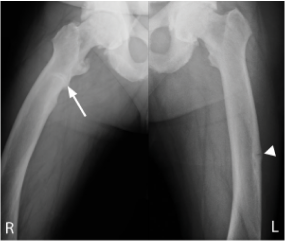

X-rays

44 years of age: diffuse increased density of iliac wings and lumbosacral spine; bilateral enthesopathic calcifications extending from the superior acetabular walls.

44 years of age: right subtrochanteric pseudofracture (arrow) incomplete along the medial cortical region.

44 years of age: pseudofractures in the subtrochanteric right femur (arrow) and mid-left femoral diaphysis (arrow head); healing stress fracture present in left femoral neck medial cortex; enthesophytes and bilateral hip osteoporosis.

The patient exhibited XLH signs and symptoms throughout childhood and young adulthood, and was not diagnosed until his mid-40s.

Diagnosis and initial treatment

Disease progression (post-treatment)

44 years of age

After XLH diagnosis, underwent left hip replacement surgery

46 years of age

Developed worsening left shoulder and knee pain requiring multiple orthopedic visits for steroid injections

47 years of age

Underwent knee replacement therapy evaluation

49 years of age

Underwent left knee replacement; advised a right total knee replacement was needed as well

3 months later: Alternate therapeutic options were explored

The patient initiated oral phosphate and active vitamin D and was compliant. Symptoms of XLH continued to progress, leading to a search for alternative treatment options.

Laboratory results

| Test (reference range** unit) | 44 Years (results) | 47 Years (results) |

|

Serum phosphorus (2.4-5.7 mg/dL) |

2.1 | 2.1 |

| 1,25(OH)2D (20-80 ng/mL) | 31 | 25 |

| 25(OH)D (25-80 ng/mL) | 33 | 37 |

| BSAP (6.5-20.1 mcg/L) | 39.2 | 32 |

| PTH (16-77 pg/mL) | 95 | 48 |

| Creatinine (0.72-1.25 mg/dL) | 0.83 | 1.12 |

| FGF23 (<180 RU/mL) | 73 | 383 |

**Indicates normal range, age, and sex matched. Note that normal range values may vary depending on reference dataset. These ranges were provided by the treating physician. Colored values are outside of the normal range provided by the physician and can raise suspicion of XLH.

1,25(OH)2D=1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D; 25(OH)D=25-hydroxyvitamin D (calcifediol); BSAP=bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, also known as BAP; FGF23=fibroblast growth factor 23; PTH=parathyroid hormone.

Connect their symptoms and accurately diagnose with the right tests.

Learn more about how to accurately diagnose XLH through testing.

Manage XLH early to prevent progressive bone damage.

Set up time with a representative to talk more about XLH, or sign up for news and information about XLH.

References:

1. Dahir K, Roberts MS, Krolczyk S, Simmons JH. X-linked hypophosphatemia: a new era in management. J Endocr Soc. 2020;4(12):bvaa151. doi:10.1210/jendso/bvaa15 2. Gaucher C, Walrant-Debray O, Nguyen TM, Esterle L, Garabédian M, Jehan F. PHEX analysis in 118 pedigrees reveals new genetic clues in hypophosphatemic rickets. Hum Genet. 2009;125(4):401-411. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0631-z 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical growth charts. 2 to 20 years: girls. Published May 30, 2000. Accessed May 21, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/data/set2clinical/cj41c072.pdf 4. Ruppe MD. X-linked hypophosphatemia. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al., eds. GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; February 9, 2012. Updated April 13, 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK83985/ 5. Carpenter TO, Imel EA, Holm IA, Jan de Beur SM, Insogna KL. A clinician’s guide to X-linked hypophosphatemia. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(7):1381-1388. doi:10.1002/jbmr.340 6. Hamilton AA, Faitos S, Jones G, Kinsley A, Gupta RN, Lewiecki EM. Whole body, whole life, whole family: patients’ perspectives on X-linked hypophosphatemia. J Endocr Soc. 2022;6(8):bvac086. doi:10.1210/jendso/bvac086